To date, the purchase of competitors’ trademarks as keywords that activate sponsored links has spurred more than 100 trademark infringement lawsuits in the U.S. and Europe. In all but a handful of those suits, courts have ruled in favor of the defendant, leaving plaintiff trademark owners largely without recourse.

However, for many business owners, the question remains: Does targeting your competitor’s name in Google Ads constitute trademark infringement? Below, you’ll find a discussion of the history of trademarks as search engine keywords, the merits of the legal arguments for and against infringement, and several seminal cases on the matter.

About Google Ads

At the end of the day, all companies are seeking prominence and priority in search results, but optimizing sites organically for certain keywords takes considerable time and effort. To bypass (or supplement) this step, companies can instead purchase ad placement on specific keywords from Google or other search engines so their site appears on the first page of search results.

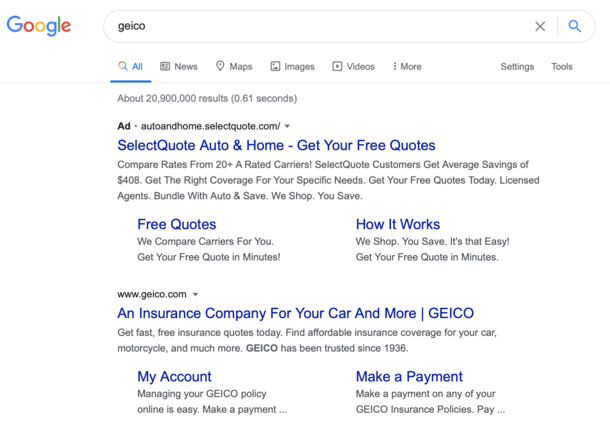

Typically, companies purchase a keyword or phrase that describes their products or services. As you can see in the screenshot above, sites that appear via Google Ads have the same general look as ‘normal’ results, making it potentially difficult to distinguish ads from organic results. The only notation is the small ‘Ad’ text next to the URL.

Trademarks as Keywords

In 2004, Google began selling trademarks as keywords, but it wasn’t until 2009 that it permitted the use of trademarks in the text of ads. The ensuing controversy resulted in a spate of trademark litigation, with companies like American Airlines, Geico, and Rosetta Stone suing Google for infringement.

These cases have since settled, and Google continues to sell trademarks as Google Ads in the U.S. Interestingly, though, in most other countries—including China, Australia, and most of the European Union—Google restricts or prohibits the use of trademarks in ad text.

The Argument for a Finding of Infringement

Because federal statutes are silent on the use of trademarks as keywords, the likelihood of confusion provides the doctrinal context for the resulting infringement suits. To recover, then, plaintiffs must establish a likelihood of confusion as to “affiliation, sponsorship, or association” (J. Thomas McCarthy, McCarthy on Trademarks and Unfair Competition, 4th ed. 2012).

That is, the plaintiff must demonstrate that the defendant’s use of the mark caused confusion about the source (some consumers believe the defendant’s goods to be the plaintiff’s), sponsorship (the plaintiff endorses the products of the defendant), or affiliation (the plaintiff and defendant are associated entities).

American Airlines’ Argument

For example, in American Airlines’ suit against Google, Google had sold the airline’s name as a keyword so that it triggered sponsored-link ads on the search results pages. Some of these ads led to the sites of competing airlines, which American argued causes confusion as to the source (e.g. a consumer purchased tickets through Delta believing it was American’s site).

To meet the burden of proof, American had to show that an appreciable number of consumers are likely to be confused if the defendant’s activities persist. Survey evidence is helpful but not necessary here, with most courts unswayed by figures of less than 20 percent of consumers being confused.

The Argument Against a Finding of Infringement

Defendants in these suits argue that no legally actionable initial interest confusion exists, and courts have overwhelmingly agreed. Courts look to the click-through rate (CTR) of sponsored ads as a proxy for survey evidence of consumer confusion. In other words, they examine how many consumers, after searching for the trademark, clicked an ad from a competitor that appeared in the results.

Because few ads ever achieve CTRs of more than three percent, this figure typically suggests “de minimis activity probative of an absence of initial interest confusion”. In plain English – the big majority of folks aren’t confused. Legal scholars have pointed out that this standard creates an almost insurmountable barrier for plaintiffs in keyword advertising lawsuits.

Google’s Argument

In the American Airlines suit, Google contended that its “invisible use” of trademarks—invisible because they do not appear in the text of ads—cannot constitute infringement because it is not technically trademark use under U.S. law. Google likened its practices to placing generic medications next to name brands in drug stores and purchasing billboards ads near those of competitors.

Companies in Google’s position argue that consumers who search for trademarks have already pre-selected their retailer and thus will be vigilant in clicking results associated with that company. Furthermore, they argue that consumers are savvy enough to recognize differences between organic results bearing American Airlines’ name and sponsored ads bearing the names of other airlines.

Landmark Case: 1-800 Contacts v. Lens.com

In July of 2013, a six-year court battle came to a close when the Tenth Circuit held that Lens.com was not liable for misdirecting consumers to click on Lens.com links after searching for 1-800 Contacts. Lens.com bought Google Ads keywords like “1-800 contact lenses,” “800 contact lenses,” “800comtacts.com,” and “800conyacts.com” that prompted sponsored ads leading to its site or the sites of its affiliates.

All told, Lens.com made $20 of profit (no, that’s not a typo) from the competitive keyword ads, and its affiliates received 1,800 clicks from the ads, worth about $40,000 by the most generous estimates. Still, 1-800 Contacts spent more than $650,000 suing for infringement only to have the court rule in Lens.com’s favor. The court’s decision turned largely on the CTR for the ads, which was 1.5 percent for Lens.com, far below the court’s threshold of 20 percent to establish confusion.

There Are Limits

Google does provide resources for trademark owners who feel as though an advertiser is unjustly using their mark in search ads. Read more in these resources:

The Final Verdict: It’s Difficult to Prove Infringement

While plaintiffs’ legal arguments in these infringement claims are not without merit, the bottom line is that suing over competitive keyword advertising is often financially irrational and mostly futile. The trivial amount of revenue and clicks generated by these ads is hardly worth fighting over, especially when most courts have been unsympathetic to trademark owners thus far.

The good news is that for small- and mid-sized businesses, Google will not investigate or restrict the use of famous trademark terms in Google Ads keywords. That is not to say that there is no risk of trademark infringement at all when using another company’s trademark term; however, the Tenth Circuit ruling in 1-800 Contacts v. Lens.com certainly does not bode well for those attempting to claim trademark infringement in similar cases.